This week, voters in the EU will be heading to the polls and electing a new European Parliament. As the campaigning gears up, the outgoing Commission’s biggest legacy – the Green Deal – is drawing some criticism. Euractiv went as far as calling it “The number one election punching bag…”.

Rhetoric about dismantling the Green Deal is just that – rhetoric. Achieving climate neutrality by 2050 is not up for debate in the EU, nor should it be. The decision to reach climate neutrality by 2050 has been taken and even enshrined in law. The debate is over. The requirement now is to rise to the challenge, not beat down the objective.

In fairness, the largest parliamentary groups do recognise that the EU has agreed on the ‘what’ (climate neutrality) and the ‘when’ (by 2050). However, the ‘how’ is still contested, and there are multiple pathways to reaching climate neutrality. The European People’s Party (EPP), in their manifesto, note that we “must make climate policy go hand in hand with our economy and society.” The Socialists’ call for a new “green social deal” that, among other things, will “…secure affordable and reliable energy supply for all.” All indicators point towards the next mandate focusing on securing a climate-neutral, affordable, and competitive economy.

That brings us to bioenergy. I’ve argued previously that unrealistically low assumptions about the amount of sustainable bioenergy available risks over-rationing, forcing sectors onto more costly pathways. In this post I wanted to take a look at some concrete examples.

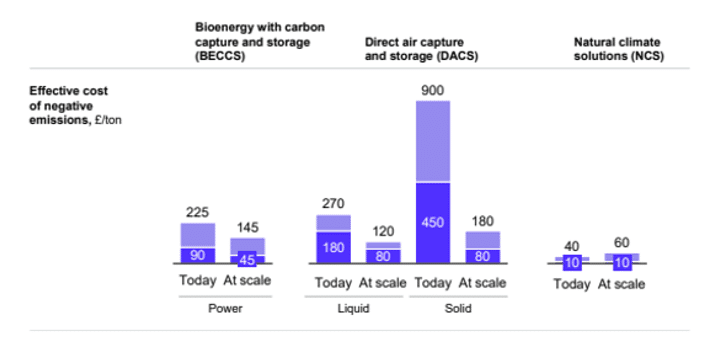

The EU Commission has concluded that by 2040, 280 million tonnes of carbon will need to be captured, with almost half needing to come from biogenic sources or directly from the atmosphere. There are only two viable pathways for achieving this: Bioenergy Carbon Capture and Storage (BECCS) and Direct Air Capture and Storage (DACCS). Both of these will certainly be needed, but in a hypothetical world where there isn’t enough bioenergy, the amount of BECCS would decline. As you can see in Figure 1 (from the technology-neutral Coalition for Negative Emissions), the cost of this could be significant with, at today’s cost, the cheapest DACCS option costing 20% more per ton of carbon removed than BECCS.

Figure 1

Furthermore, BECCS projects do not just provide carbon removals, they also produce dispatchable renewable power (or heat). A study from Aurora for the Dutch Government shows that per MWh, BECCS was the cheapest non-fossil dispatchable power source (assuming 4,500 full load hours). Even when just considering power generation, the cost-effectiveness is still evident.

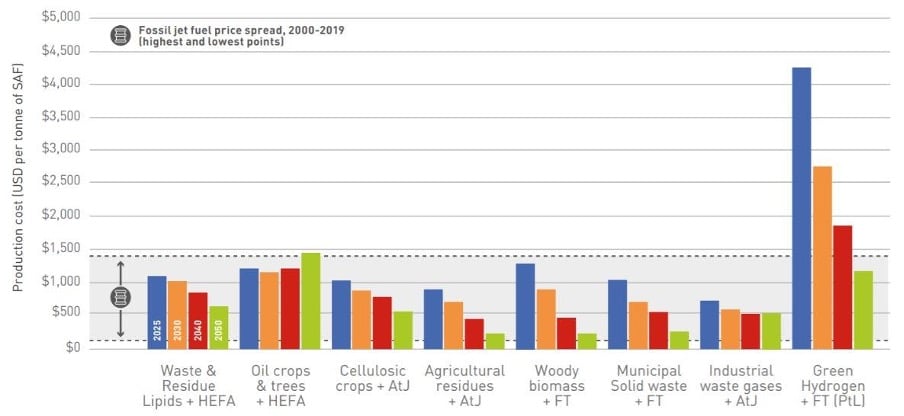

A similar conclusion can be made when looking at aviation. According to the Air Transport Action Group, an association of air transport value chain actors, displacing fossil fuels for air travel is considerably more cost-effective when utilizing the variety of bio-based feedstocks (see Figure 2), both today and in the future. The only non-bio-based option – green hydrogen – is roughly three times the cost of the highest-cost bio-based pathway – woody biomass. It is also worth noting that the woody biomass pathway is expected to experience the largest drop in production costs.

Figure 2

The same can be said when looking at options for decarbonizing high-temperature heat in industrial processes. Direct electrification can often be challenging, which leaves many industries with a choice between green hydrogen and biomass. Extrapolating numbers provided in a recent IEA Bioenergy study, biomass fuel is approximately 2.4 times cheaper than green hydrogen. This is before considering the costs involved in transportation, storage, and availability of green hydrogen. The impacts of these factors can already be seen in major industrial players such as Arcellor Mittal and the European Lime industry, which are already looking to use biomass as part of the solution.

There is no silver bullet for displacing the millions of tons of fossil fuels currently consumed in the EU. We will need a mix of technologies, and the costs associated with each are likely to fall as they reach scale. However, the above examples show that in many instances, biomass pathways can be considerably cheaper than other non-fossil alternatives. Over-rationing of biomass due to unrealistically low availability estimates could significantly impact delivering an affordable and cost-effective Green Deal.

About the author

Andrew Georgiou

Vice-President, Global Policy, USIPA

Andrew Georgiou is Vice-President for Global Policy at the US Industrial Pellet Association (USIPA), a wood energy sector trade association representing members operating in all areas of the wood pellet export industry. With almost 15 years of experience working in politics and public policy he leads USIPA’s engagement with policymakers across Europe, the US and Asia . He sits on the Board of Bioenergy Europe and takes part in a number of working groups on a broad range of biomass policy issues affecting markets across the globe.